16 Pennsylvania House Details That Might Break Today’s Construction Rules

Pennsylvania homes carry the charm of history in every corner, from their sturdy stone foundations to their elegant woodwork.

But many features that made these houses special decades ago would raise red flags with modern building inspectors.

Today’s construction codes prioritize safety, energy efficiency, and accessibility in ways that simply weren’t considered when these beautiful old homes were built.

1. Stone And Brick Foundation Walls

Builders once relied on stacked stone and brick to support entire homes across Pennsylvania.

These foundations served families for generations, holding up beautifully through countless winters. Moisture seeps through porous materials over time, creating dampness issues in basements.

Modern codes demand poured concrete foundations with proper waterproofing membranes.

Concrete offers superior structural strength and resists water infiltration far better than old masonry.

Inspectors today would flag these charming stone walls as insufficient for new construction.

Homeowners restoring historic properties often face tough decisions about preserving character versus meeting standards.

Steel reinforcement and drainage systems can help, but full replacement sometimes becomes necessary.

The craftsmanship in these old foundations remains impressive despite not meeting current requirements.

2. Knob And Tube Electrical Wiring

Ceramic knobs and hollow tubes once guided electrical current through walls and ceilings safely.

This system worked brilliantly when homes had fewer electrical demands and limited appliances.

Air circulation around wires helped dissipate heat, preventing fires in simpler times.

Today’s codes require grounded three-wire systems with circuit breakers for enhanced protection.

Modern homes consume exponentially more electricity than builders could have imagined a century ago.

Knob and tube lacks the grounding that protects people from shocks and equipment from surges.

Insurance companies often refuse coverage or charge higher premiums for homes with this wiring.

Replacing it means opening walls and ceilings, creating significant renovation expenses.

The system represents ingenious early electrical engineering that simply cannot handle contemporary needs.

3. Cast Iron And Galvanized Steel Pipes

Heavy cast iron pipes carried waste water through homes for decades without complaint.

Galvanized steel brought fresh water to faucets and fixtures throughout Pennsylvania neighborhoods.

These materials seemed indestructible when plumbers first installed them in early twentieth-century construction.

Corrosion gradually narrows pipe interiors, reducing water pressure and causing eventual failure.

Modern codes favor PVC for drainage and PEX or copper for supply lines.

These newer materials resist corrosion, install faster, and cost less than traditional metal piping.

Homeowners discover problems when rust-colored water flows from taps or drains back up mysteriously.

Replacing plumbing means invasive work that disrupts daily life for weeks at a time.

The durability of old pipes impresses, but their lifespan eventually expires in every home.

4. Asbestos And Vermiculite Insulation

Fluffy asbestos fibers once promised perfect insulation against Pennsylvania’s harsh winters.

Vermiculite from contaminated mines ended up in countless attics across the state.

Nobody understood the health risks these materials posed when contractors sprayed them liberally.

Microscopic fibers cause serious lung diseases including mesothelioma when people breathe them.

Current codes ban asbestos entirely and require careful handling of any remaining material.

Fiberglass, mineral wool, and spray foam provide safer alternatives that insulate just as effectively.

Removal requires certified professionals wearing protective equipment to prevent fiber dispersal throughout homes.

Testing confirms whether insulation contains dangerous materials before renovation work begins.

The tragic legacy of these materials reminds us that innovation sometimes carries unforeseen consequences.

5. Undersized Basement Window Openings

Tiny basement windows let in minimal light while keeping out cold Pennsylvania air.

Builders saw basements as utility spaces rather than living areas requiring emergency exits.

These narrow openings might measure just twelve by twenty inches in older homes.

Fire codes now mandate egress windows large enough for firefighters to enter and occupants to escape.

Minimum dimensions typically require at least 5.7 square feet of opening area.

The bottom of the window must sit no higher than 44 inches above the floor.

Finishing basements for living space demands installing compliant windows with proper wells outside.

Cutting through foundation walls represents major construction requiring permits and professional expertise.

Safety concerns override aesthetic preferences when building inspectors evaluate basement sleeping areas.

6. Steep And Narrow Staircase Construction

Carpenters built staircases as steep as ladders to save precious floor space.

Narrow treads barely accommodated adult feet, while high risers created challenging climbs.

These space-saving designs made sense when homes had smaller footprints and limited square footage.

Current codes specify maximum riser heights of 7.75 inches and minimum tread depths of 10 inches.

Consistent dimensions prevent trips and falls by creating predictable stepping patterns.

Handrails must extend the full length at heights between 34 and 38 inches.

Older staircases feel treacherous to modern users accustomed to gentler slopes and wider steps.

Renovating means either rebuilding entirely or obtaining variances for historic properties.

The craftsmanship in antique staircases deserves admiration even when dimensions fail safety standards.

7. Low Ceiling Heights Throughout

Ceilings hovered just inches above occupants’ heads in many Pennsylvania homes.

Seven-foot ceilings conserved heat by reducing the volume of air requiring warming.

Shorter people of previous generations felt less cramped than modern inhabitants do today.

Building codes now require minimum ceiling heights of seven and a half feet in habitable rooms.

Basement ceilings must clear at least seven feet to count as finished living space.

Taller standards improve air circulation and create more comfortable psychological environments for occupants.

Raising ceilings means jacking up entire structures or excavating beneath foundations at enormous expense.

Historic homes receive some flexibility, but finished spaces still need reasonable headroom.

The cozy feeling of low ceilings appeals to some, while others feel claustrophobic.

8. Missing Or Improperly Located Smoke Detectors

Smoke detectors simply did not exist when most Pennsylvania historic homes were constructed.

Early battery-powered units arrived in the 1970s, but installation remained optional for years.

Many older homes still lack adequate coverage in critical areas throughout their layouts.

Current codes mandate interconnected smoke alarms in every bedroom, outside sleeping areas, and on each level.

Hard-wired units with battery backup ensure functionality even during power outages.

Devices must meet specific sensitivity standards and include both ionization and photoelectric detection.

Retrofitting older homes with proper coverage requires running new wiring through walls and ceilings.

Wireless interconnected units offer easier installation options for renovation projects.

These life-saving devices have prevented countless tragedies since becoming standard equipment in all homes.

9. Inadequate Mechanical Ventilation Systems

Fresh air entered homes through cracks and gaps rather than through designed ventilation systems.

Drafty construction provided accidental air exchange that prevented moisture buildup and stale air.

Modern weatherization seals homes tightly, trapping humidity and pollutants inside without mechanical help.

Building codes now require exhaust fans in bathrooms and kitchens to remove moisture and odors.

Whole-house ventilation systems exchange stale indoor air with fresh outdoor air continuously.

Proper ventilation prevents mold growth, improves indoor air quality, and protects building materials.

Adding ventilation to older homes means installing ductwork and cutting holes through exterior walls.

Bathroom fans must vent outdoors rather than into attics, where moisture causes damage.

Energy recovery ventilators capture heat from exhaust air to improve efficiency.

10. Unlined Chimneys And Non-Compliant Fireplaces

Brick chimneys rose through Pennsylvania homes without protective liners inside their flues.

Masons simply stacked bricks with mortar, trusting construction to contain heat and smoke.

Fireplaces opened directly into rooms with minimal clearance to surrounding combustible materials.

Modern codes require stainless steel or clay tile liners to protect masonry from corrosive combustion gases.

Specific clearances separate fireboxes from wood framing, typically 2 inches for masonry fireplaces.

Glass doors, spark screens, and proper dampers prevent embers from escaping into living spaces.

Relining old chimneys costs thousands but prevents house fires and carbon monoxide poisoning.

Inspectors use cameras to examine flue conditions before approving fireplace use.

The romantic appeal of crackling fires must balance against serious safety considerations.

11. Poorly Constructed Decks And Porches

Homeowners built decks and porches using whatever lumber and methods seemed reasonable at the time.

Posts sat on concrete blocks rather than proper footings below frost lines.

Ledger boards attached to houses with insufficient fasteners or without proper flashing.

Current codes specify footing depths, beam spans, joist spacing, and fastener schedules for safe deck construction.

Pressure-treated lumber or naturally rot-resistant species must resist decay in outdoor applications.

Guardrails must reach 36 inches high with balusters spaced to prevent children from slipping through.

Deck collapses cause serious injuries when inadequate construction fails under the weight of gatherings.

Inspectors examine ledger board attachments carefully since failures there prove particularly catastrophic.

Rebuilding older decks to current standards protects families and increases property values.

12. Combustible Roofing Materials Like Wood Shakes

Cedar shakes provided beautiful, natural roofing that aged gracefully on Pennsylvania homes.

The material breathed, shedding water while allowing moisture to escape from the roof assemblies.

Skilled roofers layered shakes with precision, creating watertight protection that lasted decades.

Fire codes now restrict or prohibit wood roofing in many jurisdictions due to wildfire risks.

Asphalt shingles, metal roofing, and synthetic materials offer fire-resistant alternatives with similar aesthetics.

Class A fire ratings represent the highest level of fire resistance for roofing products.

Replacing wood shakes often reveals underlying roof damage from years of moisture penetration.

Some historic districts still permit wood roofing with fire-retardant treatments applied during manufacturing.

The natural beauty of wood appeals to traditionalists despite practical and regulatory challenges.

13. Lead-Based Paint On Interior Surfaces

Painters applied lead-based paints liberally throughout homes built before 1978.

The heavy metal made the paint durable, washable, and resistant to fading over time.

Beautiful colors lasted for decades without the chalking and deterioration of inferior formulations.

Lead poisoning causes devastating developmental damage in children who ingest paint chips or dust.

Federal regulations now prohibit lead paint in residential applications and require special procedures during renovation.

Certified contractors follow strict protocols to contain dust and dispose of waste properly.

Testing identifies lead paint before renovation work begins, allowing for appropriate safety measures.

Encapsulation, enclosure, or removal represent three approaches to managing lead paint hazards.

The tragic legacy of lead paint reminds us that convenience and performance sometimes hide terrible costs.

14. Asbestos Siding And Exterior Materials

Asbestos cement siding promised fireproof, weather-resistant exterior protection for Pennsylvania homes.

Manufacturers pressed cement and asbestos fibers into shingles that mimicked wood grain beautifully.

The material never rotted, resisted insects, and required minimal maintenance for decades.

Health risks from asbestos exposure led to complete bans on its use in building materials.

Intact siding poses minimal risk, but cutting, breaking, or removing it releases dangerous fibers.

Professional abatement contractors use wet methods and protective equipment during removal projects.

Many homeowners choose to cover asbestos siding with vinyl rather than removing hazardous material.

Testing confirms asbestos content before any work begins on suspected materials.

The durability and fire resistance that made asbestos popular cannot overcome its deadly health effects.

15. Non-Compliant Stairway Handrails And Guards

Decorative handrails prioritized beauty over functionality in historic Pennsylvania homes.

Wide, flat rails looked elegant but proved difficult to grasp during falls.

Heights varied inconsistently, and many staircases lacked rails entirely on one side.

Current codes require handrails between 34 and 38 inches high with circular cross-sections.

Graspable profiles allow hands to wrap around rails for secure holds during slips.

Guards must prevent spheres larger than four inches from passing through to protect children.

Adding compliant handrails to antique staircases challenges craftspeople to blend safety with historic character.

Both sides of stairs wider than 44 inches require rails for code compliance.

The balance between preservation and safety creates ongoing debates in historic home renovation.

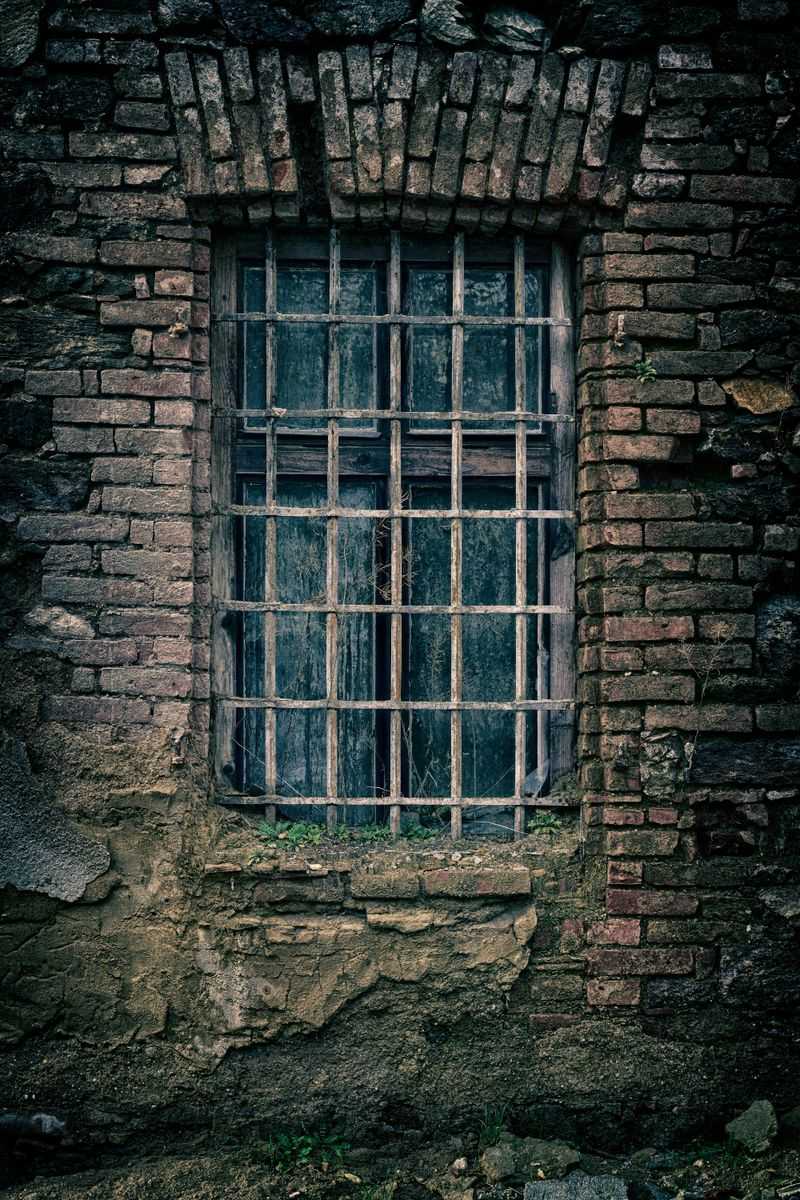

16. Window Security Bars Without Quick-Release Mechanisms

Metal bars protected windows from intruders in urban Pennsylvania neighborhoods.

Homeowners welded or bolted bars permanently across openings to prevent break-ins.

The security measures worked effectively but created deadly traps during fires.

Building codes now prohibit fixed bars on egress windows required for emergency escape.

Quick-release mechanisms must open from inside without keys or special tools.

Bars must swing away or remove easily, even when occupants feel disoriented by smoke.

Tragic fires killed families trapped behind security bars they installed for protection.

Modern systems balance security with safety through approved release mechanisms and proper installation.

The psychological comfort of bars must never compromise the ability to escape danger quickly.