This Incredible Underground Garden In California Was Built To Escape The Sun

Beneath Fresno’s scorching summer heat lies a hidden world that few expect to find — a hand-carved underground sanctuary built entirely by one man’s vision and persistence.

What began as a practical solution to California’s unforgiving climate slowly evolved into an architectural wonder unlike anything else in the state.

Over the course of four decades, Baldassare Forestiere dug through dense hardpan rock using only basic tools, shaping a subterranean network of passageways, courtyards, and living spaces designed to stay naturally cool year-round.

But this was never just about escape from the heat.

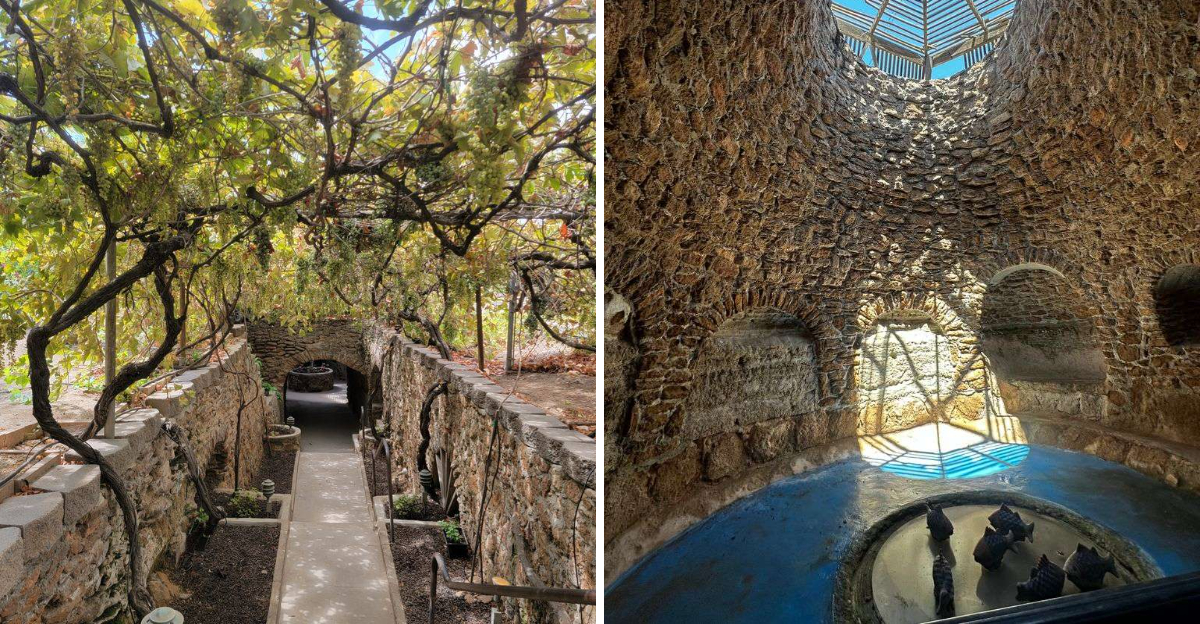

Forestiere planted fruit trees, grapevines, and gardens below the surface, creating a flourishing oasis where sunlight filters in through carefully engineered openings.

Today, the Forestiere Underground Gardens stand as both a historic landmark and a testament to human determination – proof that resilience and creativity can transform even the harshest landscapes.

Walking through the winding tunnels and sunlit chambers feels less like touring a structure and more like discovering a secret world hidden in plain sight, one that continues to surprise visitors more than a century after it first took shape.

1. A Sicilian Immigrant’s Bold Vision

Baldassare Forestiere arrived in America with dreams shaped by the volcanic soil and ancient architecture of his native Sicily.

Born in 1879, he carried knowledge of underground structures from the wine cellars and catacombs of his homeland.

When he purchased property in Fresno around 1906, he expected to cultivate citrus groves in fertile California soil.

The reality proved brutally different.

His land consisted of hardpan sedimentary rock that extended several feet below the surface, making traditional farming nearly impossible.

Summer temperatures regularly exceeded 100 degrees, creating conditions that felt unbearable for someone accustomed to Mediterranean breezes.

Rather than abandon his investment, Forestiere decided to work with the rock instead of against it. His solution emerged from memories of cool underground spaces back home.

He began digging downward, creating rooms that would provide relief from the relentless heat. What started as a practical response to climate grew into a lifelong artistic and horticultural endeavor.

His vision expanded year by year as he discovered the possibilities hidden beneath the unforgiving surface. The project consumed the next forty years of his life until his death in 1946.

2. Hand-Carved Chambers Spanning Decades

Forestiere wielded picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows as his primary construction equipment throughout four decades of excavation.

He worked alone most of the time, with only a pair of mules to help haul rock and soil to the surface. The physical demands of this labor were staggering, yet he maintained a steady pace year after year.

Each chamber required removing tons of hardpan before it could serve any purpose. The complex at 5021 W Shaw Ave, Fresno, CA 93722 eventually encompassed approximately 10 acres of underground space across three distinct levels.

The shallowest rooms sit about 10 feet below ground, while the deepest chambers reach 23 feet down. Between these levels, Forestiere created a middle tier at roughly 20 feet depth.

The total network includes 65 rooms connected by passages and courtyards, each serving specific functions in his underground home. Room purposes ranged from practical to recreational.

He carved out a summer bedroom where cooler temperatures provided comfortable sleep, and a separate winter bedroom positioned to capture more warmth.

A functional kitchen included workspace and storage carved directly into the rock.

He even created a fishpond and a parlor complete with a fireplace, demonstrating how thoroughly he adapted underground living to meet all his needs.

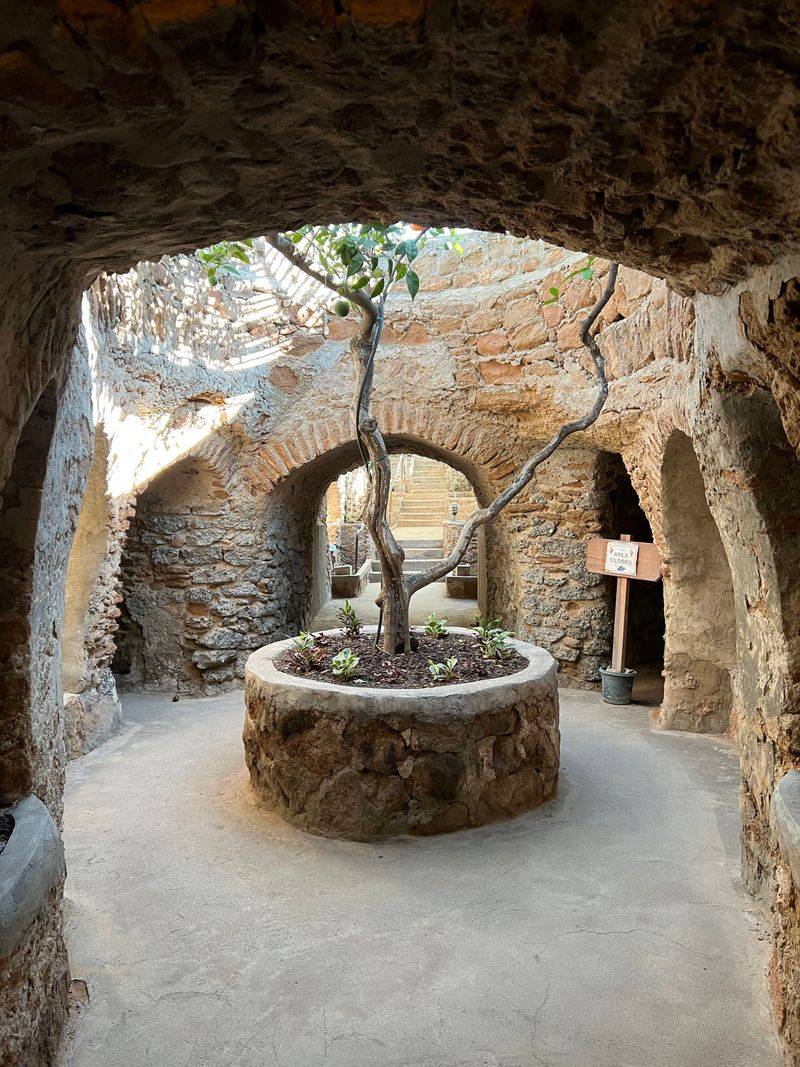

3. Ingenious Skylight And Ventilation System

Natural light reaches the underground chambers through carefully positioned skylights that Forestiere cut at strategic angles.

These openings vary in size from small apertures to large conical shafts that funnel daylight deep into the complex. The placement of each skylight considered the sun’s path throughout the day and across seasons.

Some rooms receive direct sunlight for several hours, while others enjoy softer diffused light filtered through multiple openings. Temperature control happens passively through this same network of vertical shafts.

Hot air naturally rises and escapes through the upper openings while cooler air settles in the lower chambers. This convection process creates constant gentle circulation without mechanical assistance.

The system maintains temperatures 10 to 20 degrees cooler than the surface during summer months, providing genuine relief from Fresno’s extreme heat.

Winter conditions reverse this advantage as the underground spaces retain warmth more effectively than surface structures.

The thermal mass of surrounding earth acts as insulation, moderating temperature swings in both directions.

Forestiere could move between his summer and winter bedrooms to optimize comfort throughout the year.

His ventilation design anticipated modern passive cooling principles by several decades, proving that observation and experimentation can match formal engineering education in practical results.

4. Fruit Trees Growing Below Ground

Forestiere achieved what seemed impossible by successfully cultivating fruit-bearing trees in underground chambers.

He planted citrus varieties along with other fruits in soil-filled courtyards open to the sky through carefully sized apertures. The trees sent roots down into the earth while their canopies grew upward toward the light.

This arrangement protected the plants from frost damage during winter nights while allowing adequate sunlight for photosynthesis and fruit production.

His horticultural experimentation extended to grafting multiple varieties onto single rootstocks. One tree might produce oranges on some branches, lemons on others, and grapefruits on still more.

This technique maximized diversity within limited space while showcasing his agricultural knowledge.

The gardens eventually included kumquats, loquats, jujubes, and various berries alongside more common citrus fruits.

Each species required specific attention to light levels and growing conditions. Some of these original plantings continue thriving more than a century after Forestiere placed them in the ground.

Their longevity demonstrates how well the underground environment protects against weather extremes that stress surface orchards.

The trees benefit from consistent moisture levels and protection from wind that can damage blossoms and young fruit.

Modern visitors can see and sometimes taste fruit from these ancient specimens, connecting directly with Forestiere’s living legacy.

5. Three Levels Of Underground Space

The vertical organization of the complex reflects Forestiere’s evolving understanding of how to use depth strategically.

The uppermost level at 10 feet below surface offers the easiest access and receives the most natural light. He positioned rooms here that benefited from brighter conditions and more frequent use.

This level connects most directly to the surface through shorter passages and stairways that require less climbing.

Twenty feet down, the middle level provides a buffer zone between the surface extremes and the deepest chambers. Temperatures here remain more stable than above but stay warmer than the lowest areas.

Forestiere used this intermediate depth for rooms where moderate conditions suited their purposes.

The middle level also serves as a transitional space in the circulation pattern, with passages leading both up and down.

At 23 feet below ground, the deepest chambers offer maximum insulation from surface temperatures. These rooms maintain the coolest conditions during summer and the most stable warmth in winter.

Forestiere reserved this level for spaces where consistent temperature mattered most, including certain storage areas and his summer bedroom.

The three-level system allowed him to move vertically through the complex to find optimal conditions for any activity or season, essentially creating a personalized climate control system carved from solid rock.

6. Roman-Inspired Architectural Elements

The architectural language Forestiere employed drew heavily from classical Roman design principles he had absorbed in Italy.

Arches appear throughout the complex, providing both structural support and aesthetic grace to the carved spaces.

These curved forms distribute weight effectively while creating visual rhythm as visitors move through the passages. Columns rise at key points, some purely decorative and others bearing loads from the earth above.

Domed ceilings crown several of the larger chambers, echoing the grand public spaces of ancient Rome.

Forestiere shaped these curves entirely by hand, removing rock bit by bit until the proper form emerged.

The precision required for stable domes without modern engineering tools speaks to his intuitive understanding of structural forces.

Each dome serves a functional purpose beyond beauty, helping to direct airflow and distribute pressure evenly.

The hardpan sedimentary rock itself became both material and canvas for his architectural vision.

Unlike softer soil that would require extensive support, the hardpan held its shape once carved, allowing for more ambitious designs. Forestiere left tool marks visible in some areas while smoothing others to a polish.

His work transformed raw geology into livable art that has endured for over a century without significant structural failure.

7. National Historic Recognition

The significance of Forestiere’s achievement gained official acknowledgment in 1977 when the underground gardens earned placement on the National Register of Historic Places.

This federal designation recognizes properties that possess exceptional historical, architectural, or cultural value to the nation.

The listing process requires extensive documentation and evaluation by preservation professionals who assess a site’s integrity and importance.

For the gardens to receive this honor validated their status as genuinely remarkable rather than merely quirky.

One year later in 1978, the State of California added its own recognition by designating the site as California Historical Landmark No. 916. This state-level honor carries its own prestige and legal protections.

The landmark designation helps ensure that future development in the area considers the gardens’ historical importance. It also raises public awareness about the site’s existence and encourages preservation efforts.

Both designations came decades after Forestiere’s death, representing posthumous recognition of his extraordinary accomplishment.

These official honors classify the gardens as an unconventional example of vernacular architecture – structures built by individuals without formal architectural training, using traditional methods and local materials.

The site demonstrates how personal creativity and determination can produce works of lasting cultural value.

The designations also facilitate potential funding for preservation and maintenance, helping to protect this unique heritage for future generations to experience and study.

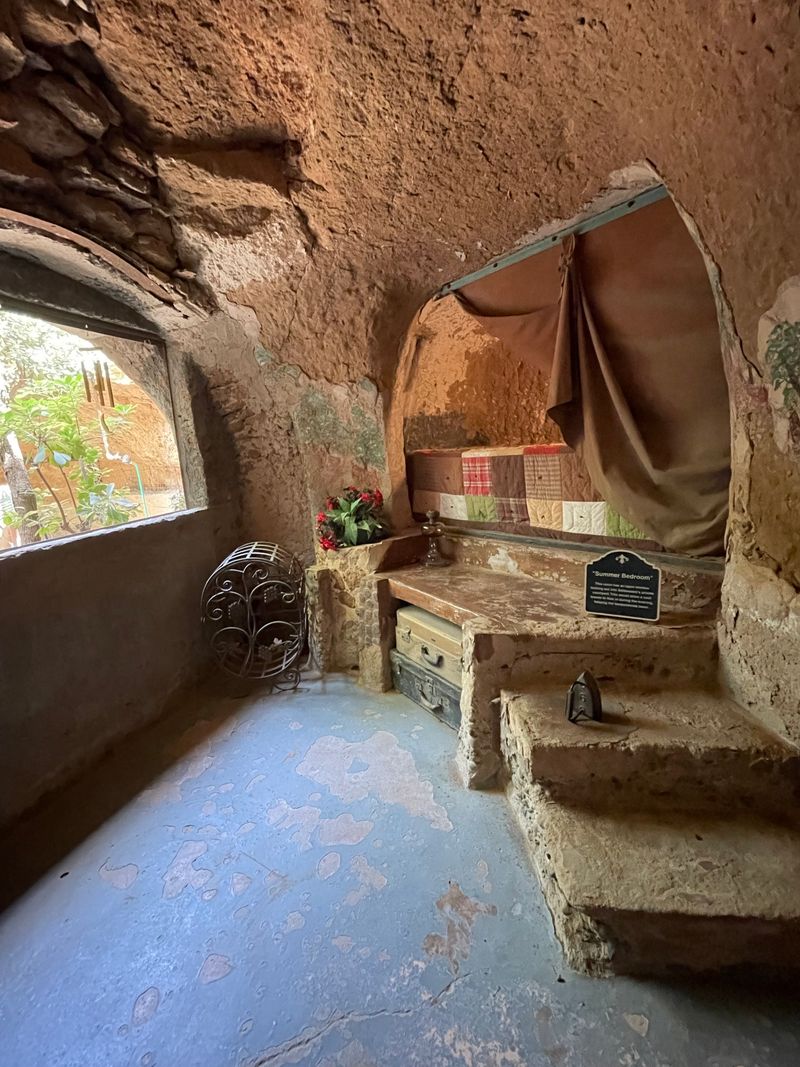

8. Living Quarters Carved From Rock

Forestiere didn’t simply create a novelty attraction – he built a fully functional home where he actually lived for decades. His sleeping arrangements included two separate bedrooms optimized for seasonal comfort.

The summer bedroom sat deeper in the complex where temperatures remained coolest during hot months. He could retreat there during the most oppressive heat and sleep comfortably without mechanical cooling.

The winter bedroom occupied a different position where it captured and retained more warmth during colder periods.

The kitchen he carved provided genuine workspace for daily meal preparation. Counter surfaces and storage areas emerged directly from the rock walls, shaped to accommodate his needs.

He installed plumbing to bring water into the underground space, solving one of the major challenges of subterranean living.

The kitchen’s position in the complex allowed smoke from cooking to escape through ventilation shafts while keeping the living areas comfortable.

This practical design showed his attention to everyday functionality alongside grander architectural ambitions. A bath chamber addressed personal hygiene needs with the same creative problem-solving.

The parlor with its fireplace offered a social space where Forestiere could entertain the occasional visitor in unexpected underground comfort.

These living quarters weren’t primitive caves but thoughtfully designed rooms that met genuine residential needs.

He proved that underground living could provide not just survival but actual comfort and dignity when approached with sufficient ingenuity and effort.

9. Hardpan Rock As Building Material

The very obstacle that made surface farming impossible became the foundation of Forestiere’s success underground.

Hardpan consists of densely compacted sedimentary layers that form naturally over millennia through pressure and mineral deposits.

This material resists penetration by roots and water, creating a nearly impermeable barrier that frustrated his agricultural plans.

Standard farming tools barely scratched its surface, and breaking through required enormous physical effort.

Most people would have considered such land worthless for cultivation.

Once excavated, however, hardpan reveals structural properties that make it ideal for underground construction.

The material holds its shape without requiring timber supports or reinforcement that would be necessary in softer soil. Carved surfaces remain stable for decades without crumbling or erosion.

This natural strength allowed Forestiere to create arches, domes, and large open chambers that would collapse if attempted in looser earth.

The hardpan essentially provided free structural material that improved with depth. The rock’s composition also contributes to the complex’s thermal properties.

Its density and mineral content help moderate temperature fluctuations, working alongside the ventilation system to maintain comfortable conditions.

The hardpan walls absorb excess heat during the day and release it slowly at night, creating a natural temperature buffer.

What initially appeared as an agricultural curse transformed into a construction blessing, demonstrating how perspective and creativity can reverse apparent disadvantages into unique opportunities.

10. Forty Years Of Solitary Labor

From 1906 until his death in 1946, Forestiere devoted himself almost entirely to expanding and refining his underground creation.

Four decades represents an extraordinary commitment to a single project, especially one requiring such grueling physical labor. He worked primarily alone, without employees or partners to share the burden.

Each day meant descending into the earth with hand tools to chip away at solid rock, load debris into wheelbarrows, and haul it to the surface.

The repetitive nature of this work would break most people’s spirits within weeks or months. His persistence suggests a deep satisfaction that went beyond practical considerations of shelter and comfort.

The project became an artistic expression and personal mission that gave meaning to his daily existence.

He continually refined his vision, adding new chambers and features as ideas occurred to him. The work never truly finished because he always imagined improvements and extensions.

This open-ended approach allowed the project to evolve organically rather than following a fixed master plan.

The solitary nature of his labor also meant that much of his process and reasoning went unrecorded. He left no detailed journals explaining his techniques or motivations.

What remains is the physical evidence of the chambers themselves, along with some oral history collected from people who knew him.

This mystery adds to the site’s fascination while making it harder to fully understand his methods and intentions.

11. Public Tours And Educational Access

Today the Forestiere Underground Gardens welcome visitors through guided tours that interpret the site’s history and significance.

The tours provide the only public access to the complex, as unsupervised exploration would pose safety risks and potential damage to this fragile historical resource.

Knowledgeable guides lead groups through the passages and chambers, explaining construction techniques and pointing out architectural details that might otherwise go unnoticed.

The guided format also allows for questions and discussion that enhance understanding beyond what signage alone could provide.

Visitors descend into a world that feels removed from modern Fresno despite sitting just below the city’s surface.

The temperature drop becomes immediately noticeable, offering tangible proof of Forestiere’s passive cooling design.

Tour routes wind through various chambers, giving glimpses of different room types and functions. Skylights punctuate the journey with shafts of natural light that illuminate the carved stone surfaces.

The presence of living fruit trees underground creates a surreal juxtaposition that photographs struggle to capture fully.

The educational value extends beyond architecture and horticulture to themes of immigrant experience, individual determination, and creative problem-solving.

School groups frequently visit to learn how one person’s vision and labor created something lasting and meaningful.

The tours operate seasonally, with specific schedules that visitors should confirm before planning a trip.

This living museum continues Forestiere’s legacy by inspiring new generations to think differently about challenges and possibilities.

12. Grafting Techniques And Agricultural Innovation

Forestiere’s horticultural skills matched his architectural abilities, particularly in the specialized technique of grafting different plant varieties onto common rootstocks.

Grafting involves joining tissue from one plant to another so they grow as a single organism.

The rootstock provides the foundation and root system, while grafted branches contribute their own fruit characteristics.

This technique allows a single tree to produce multiple types of fruit, maximizing diversity within limited space.

Successful grafting requires precise cuts, proper timing, and knowledge of which varieties can join compatibly.

His underground orchards showcased grafting at an advanced level, with individual trees bearing several distinct fruit types.

One specimen might yield oranges, lemons, and grapefruits from different branches, all drawing nutrients through the same root system.

This approach served both practical and aesthetic purposes, creating living sculptures that demonstrated botanical artistry.

The grafted trees also provided insurance against crop failure, since different varieties on one tree meant that if one type failed, others might still produce.

The success of these grafted trees underground proved that the light levels and growing conditions Forestiere created actually supported healthy plant development.

Modern horticulturists recognize the difficulty of maintaining fruit trees in such unconventional settings.

His achievements suggest both careful observation of plant needs and willingness to experiment with techniques until finding what worked.

The century-old grafted trees that still bear fruit today stand as living testimony to his agricultural expertise and the viability of his underground growing methods.

13. Legacy Of Individual Creativity

Baldassare Forestiere’s underground gardens represent something rare in American history – a major architectural achievement created entirely by one person working outside any institutional or commercial framework.

He answered to no clients, followed no building codes, and consulted no committees. This complete creative freedom allowed him to experiment and evolve his design organically over decades.

The result reflects a singular vision unmarred by compromise or commercial pressures. Such pure individual expression in architecture has become increasingly rare in modern times.

His work also challenges conventional assumptions about what constitutes valuable architecture. No prestigious firm designed these spaces, and no wealthy patron commissioned them.

Forestiere had no formal training in architecture, engineering, or horticulture.

Yet his creation has outlasted countless professionally designed buildings and continues attracting attention nearly 80 years after his death.

The gardens prove that formal credentials matter less than vision, determination, and creative problem-solving ability. They validate the potential for individuals to create meaningful works outside established systems.

The site’s preservation allows future generations to experience this testament to human ingenuity and perseverance.

Visitors leave with expanded notions of what one determined person can accomplish with simple tools and decades of focused effort.

The gardens inspire by demonstrating that remarkable achievements don’t require wealth, credentials, or institutional support – just vision, skill, and unwavering commitment to bringing an idea into physical reality through persistent labor.