A Lost North Carolina Town That Whispers Stories Of Long Ago

Beneath the Spanish moss and beside the quiet waters of the Cape Fear River lies a place frozen in time. Brunswick Town whispers tales of colonial ambition, revolutionary courage, and Civil War defenses that shaped North Carolina’s story.

Once a thriving port that rivaled Wilmington, this abandoned settlement now offers visitors a haunting glimpse into America’s past through crumbling brick walls and earthen fortifications.

Step into history and wander through the ghostly ruins where North Carolina’s past comes alive.

Colonial Dreams On The Cape Fear

Colonel Maurice Moore had vision when he accepted that 1,500-acre land grant back in 1725 from the Lord Proprietors. By June 1726, he’d carved out a settlement on the western bank of the Cape Fear River, naming it after King George I’s ancestral home of Brunswick-Lüneburg in Germany. That strategic choice of location wasn’t accidental, oceangoing vessels could navigate right up to the town’s wharves, making it perfect for trade.

The settlement grew rapidly as merchants, planters, and craftsmen recognized the economic potential of this riverside location. Within just a few years, Brunswick Town became more than a simple colonial outpost. Governor Arthur Dobbs himself chose to build his residence here, signaling the town’s importance to North Carolina’s political landscape.

Walking through Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson State Historic Site at 8884 St Phillips Rd SE in Winnabow today, you can still sense that colonial ambition. The foundations speak of permanence, of families who believed they were building something that would last forever.

Naval Stores Capital Of The Empire

Tar, pitch, and turpentine don’t sound glamorous, but they built Brunswick Town’s fortune. These naval stores were absolutely essential for shipbuilding, sealing hulls, waterproofing ropes, and preserving timber against the relentless assault of seawater. North Carolina’s longleaf pine forests produced the finest quality, and Brunswick Town became the distribution hub.

By 1772, the numbers tell an astonishing story: over 140 ships annually passed through Brunswick Town’s waters. Britain relied on this small Cape Fear settlement as its premier American supplier of naval stores. Barrels stacked high on the wharves, waiting for transport to shipyards across the Atlantic.

The economic engine hummed constantly, creating wealth for merchants and employment for workers who processed the sticky, pungent products. That prosperity funded elegant homes and the construction of impressive public buildings. When you visit the historic site today, imagine the waterfront buzzing with activity, the air thick with pine scent, and the constant creaking of ships loading precious cargo bound for distant ports.

When Governors Called Brunswick Home

Power resided in Brunswick Town during its golden years, making it North Carolina’s unofficial capital for a time. The colony’s executive branch operated from here, and the Governor’s Council occasionally convened in Brunswick’s halls. This wasn’t some backwater settlement, this was where decisions affecting the entire colony were made.

Governor Arthur Dobbs completed the magnificent Russellborough mansion in 1758, a two-story symbol of colonial authority and refined living. Governor William Tryon later occupied the same residence, though his time there would be marked by escalating tensions with colonists. The mansion’s grandeur reflected Brunswick Town’s status as a political and social center.

Today, Russellborough’s ruins at the historic site remind visitors of that vanished political importance. The brick foundations outline rooms where governors entertained guests, conducted official business, and navigated the increasingly difficult relationship between Crown and colonists. Standing where power once resided, you can almost hear the rustle of official documents and the murmur of political conversations that shaped North Carolina’s future.

St. Philip’s Church: Faith Built To Last

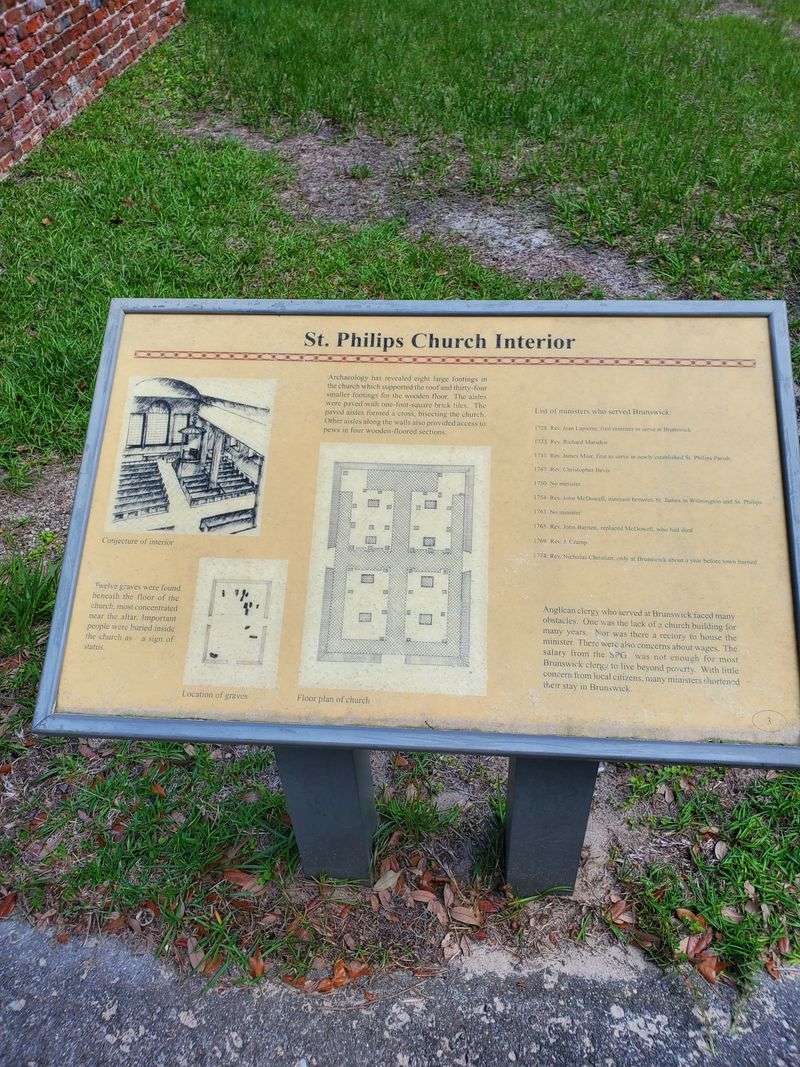

Construction began in 1754 on what would become one of the finest religious structures in colonial America. St. Philip’s Church took fourteen years to complete, with craftsmen laying bricks imported from England into walls nearly three feet thick. Those walls soared twenty-five feet high, creating an imposing presence that declared Brunswick Town’s prosperity and devotion.

The Anglican congregation spared no expense on their house of worship, understanding that a church reflected a community’s values and aspirations. Skilled masons ensured every brick was perfectly placed, creating a structure designed to stand for centuries. The church became the spiritual heart of Brunswick Town, hosting baptisms, weddings, and Sunday services that brought the community together.

Walking up to St. Philip’s ruins at 8884 St Phillips Rd SE today provokes genuine awe. Those massive brick walls still stand, defying time and abandonment with remarkable stubbornness. Touch those English bricks and you’re connecting with craftsmen who worked here over 250 years ago, building something meant to outlast them all.

The church succeeded, it remains Brunswick Town’s most recognizable landmark.

The Day Spanish Ships Arrived

September 4, 1748, started like any other day until lookouts spotted two Spanish warships anchoring off Brunswick Town. La Fortuna and La Loretta had come raiding, and panic spread through the settlement faster than wildfire. Townspeople grabbed what they could carry and fled into the surrounding forests, abandoning their homes to the invaders.

The Spanish sailors came ashore and methodically looted the defenseless town, seizing valuables and capturing enslaved individuals to take back to Spanish territories. But Brunswick Town’s militia regrouped and launched a counterattack that caught the raiders off guard. The Spanish retreated to their ships under heavy fire, suffering casualties and confusion.

Then came the explosion that sealed the raid’s failure, La Fortuna blew up near the wharves, possibly from a lucky shot hitting the powder magazine. The ship sank in the Cape Fear River waters, where it remains today. Visitors to the historic site can learn about this dramatic episode that demonstrated both Brunswick Town’s vulnerability and its residents’ determination to defend their community against foreign aggression.

Resistance Born On These Streets

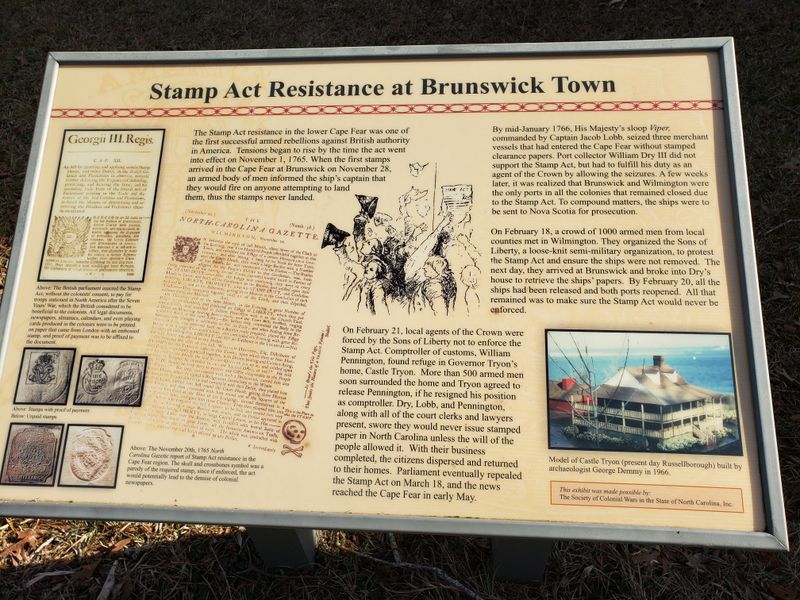

Anger simmered in Brunswick Town when news arrived of the British Stamp Act in 1765, requiring colonists to pay taxes on printed materials. This wasn’t just about money, it represented taxation without representation, a fundamental violation of colonists’ rights as British subjects. Brunswick Town’s leaders decided they’d had enough of distant Parliament making decisions that affected their daily lives.

In February 1766, local patriots took bold action that would echo through revolutionary history. They arrested royal officials attempting to enforce the hated tax, effectively nullifying the Stamp Act’s authority in the region. Then they went further, placing Governor Tryon himself under house arrest in his own mansion.

That act of defiance sent shockwaves through colonial North Carolina and beyond. Brunswick Town proved that ordinary citizens could successfully resist British authority through coordinated action. The exhibits at the visitor center detail this pivotal moment when Brunswick Town helped write the script for American independence.

Standing where those brave colonists confronted royal power, you feel the weight of that courage and its consequences for generations to come.

When The Town Went Silent

Brunswick Town’s decline happened gradually, then suddenly, like a ship slowly taking on water before the final plunge. By 1776, the thriving port had lost its vitality as Wilmington’s deeper harbor attracted more shipping traffic. Residents began relocating upriver where commercial opportunities looked brighter and the future seemed more certain.

Then British forces arrived during the Revolutionary War and put Brunswick Town to the torch. Buildings that had stood for decades went up in flames, destroying the physical infrastructure that made urban life possible. After the war ended in 1783, Brunswick Town lay mostly in ruins, a ghost of its former prosperity.

The final indignity came in 1830 when the entire townsite sold for just $4.25, less than the cost of a decent meal today. That pittance reflected how completely Brunswick Town had fallen from its position as a political and economic powerhouse. Wandering the paved trails at Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson State Historic Site, you witness the impermanence of human settlements.

Towns rise with purpose and fall when circumstances change, leaving only foundations and memories behind.

Fort Anderson Rises From The Ruins

Confederate Major General Samuel Gibbs French surveyed Brunswick Town’s ruins in the early 1860s and saw strategic opportunity. The abandoned colonial settlement occupied high ground overlooking the Cape Fear River, perfect for defending Wilmington’s vital port from Union naval forces. Construction began on Fort Anderson, an earthen fortification built literally on top of Brunswick Town’s remains.

Confederate engineers and enslaved laborers moved thousands of cubic yards of earth, creating massive embankments designed to absorb artillery fire. Cannons were positioned to command the river, creating a formidable obstacle for any Union ships attempting to reach Wilmington. The fort became a crucial link in the Confederate defense network protecting the South’s last major Atlantic port.

In February 1865, Union forces finally captured Fort Anderson after fierce fighting, contributing to Wilmington’s fall and hastening the Confederacy’s collapse. Walking Fort Anderson’s earthworks today at 8884 St Phillips Rd SE, you traverse two distinct historical periods layered atop each other. Colonial foundations peek through Civil War fortifications, creating a unique archaeological palimpsest where centuries of history literally overlap in the same soil.

Archaeologists Uncover the Past

Shovels bit into Brunswick Town’s soil in the late 1950s as archaeologists began systematic excavations that would continue through the 1960s. Buried beneath decades of vegetation and earth lay the physical evidence of colonial life—foundations, artifacts, and clues about how people actually lived in this abandoned settlement. Every discovery added pieces to Brunswick Town’s puzzle.

Excavations revealed the foundations of homes, shops, and public buildings, allowing researchers to map the town’s layout with precision. Artifacts ranging from pottery shards to buttons told stories about daily life, trade networks, and social status. The archaeological work also uncovered Fort Anderson’s defensive structures, documenting how Confederate engineers had built atop colonial ruins.

That painstaking work transformed Brunswick Town from a footnote in history books into a tangible place visitors could experience and understand. The visitor center displays many artifacts recovered during those excavations, including ceramics, tools, and military equipment. When you explore the marked foundations along the walking trail, you’re seeing the direct results of archaeological research that brought Brunswick Town’s story back from obscurity.

Some excavations continue today, promising new discoveries for future generations.

The Governor’s Mansion In Ruins

Captain John Russell started building an impressive mansion in Brunswick Town, but he never saw it completed. Governor Arthur Dobbs purchased the unfinished structure and completed construction in 1758, creating a residence befitting North Carolina’s chief executive. Russellborough, as it became known, represented the pinnacle of colonial architecture in the region—two stories of brick and ambition overlooking the Cape Fear River.

Governor William Tryon later occupied Russellborough during his turbulent tenure, hosting official functions and conducting colony business from these elegant rooms. The mansion witnessed crucial conversations and decisions during the escalating tensions between Crown and colonists. Its rooms heard arguments about taxation, representation, and the rights of British subjects in America.

Today, Russellborough’s foundation and partial walls remain among Brunswick Town’s most poignant ruins. You can trace the outline of rooms where governors once slept, entertained, and governed. Interpretive signs help visitors visualize the mansion’s former grandeur, but imagination must fill in the missing walls and furnishings.

Standing in Russellborough’s footprint, you’re occupying space where colonial North Carolina’s most powerful figures once walked and made history.

English Bricks That Refused To Fall

St. Philip’s Church walls possess an almost supernatural stubbornness, standing firm despite centuries of abandonment, weather, and even the Revolutionary War’s destruction. Those bricks came all the way from England as ship ballast, transforming practical weight into permanent architecture. The masons who laid them in the 1750s and 1760s built with skill that modern contractors admire.

Three-foot-thick walls provided excellent insulation and structural stability, but they also represented a significant investment and ambition. Importing bricks across the Atlantic wasn’t cheap, Brunswick Town’s congregation spent serious money on their church. The walls’ survival through fire, hurricanes, and over two centuries of neglect testifies to eighteenth-century craftsmanship that prioritized durability over speed.

Visitors consistently identify St. Philip’s ruins as Brunswick Town’s most photogenic and emotionally powerful feature. Those walls frame the sky where a roof once sheltered worshipers, creating a cathedral-like openness that somehow feels both melancholy and uplifting. Touch those English bricks at the historic site, and you’re connecting with craftsmen who built something that genuinely did outlast them.

The church walls remain Brunswick Town’s most defiant statement against time and abandonment.

A Living Museum You Can Walk

Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson State Historic Site offers something rare: the freedom to wander through history at your own pace without ropes keeping you at a distance. The three-quarter-mile paved trail loops through the entire site, accessible to wheelchairs, strollers, and visitors of all mobility levels. Dogs on leashes are welcome, too, making this a genuinely family-friendly historical experience.

Starting at the visitor center, you encounter excellent exhibits explaining Brunswick Town’s rise and fall, plus Fort Anderson’s Civil War role. A thirteen-minute film provides historical context, though many visitors prefer to save the indoor experience for after exploring the grounds. The trail winds past excavated foundations, interpretive signs, fort earthworks, and culminates at St. Philip’s magnificent ruins.

Reviews consistently praise the site’s peaceful atmosphere, this isn’t a crowded tourist trap but a contemplative space where history feels personal and immediate. Visitors report spotting alligators in nearby ponds, wild turkeys, and abundant bird life among the Spanish moss-draped trees. The site hosts special events like Port Brunswick Days and Christmas celebrations featuring hands-on activities like candle-making and rope-making.

Open Tuesday through Saturday from 9 AM to 5 PM, Brunswick Town invites exploration without rushing.

Where Two Wars Left Their Mark

Brunswick Town/Fort Anderson represents a rare historical overlap where Revolutionary War and Civil War history occupy the same physical space. Colonial Brunswick Town’s resistance to British authority in the 1760s and 1770s helped spark American independence. A century later, Confederate forces built Fort Anderson atop those same ruins to defend against a different American army.

That layering creates fascinating complexity for visitors willing to look beyond surface-level history. You can stand on Civil War earthworks while looking at colonial foundations, contemplating how the same land witnessed two defining conflicts in American history. The visitor center’s exhibits help untangle these interwoven stories, showing how Brunswick Town evolved from colonial port to revolutionary hotbed to Civil War fortress.

The Storm Flag displayed in the museum provides a particularly poignant artifact connecting to national tragedy, it has ties to Abraham Lincoln that staff can explain. Walking the grounds at 8884 St Phillips Rd SE in Winnabow, you experience American history as a continuous, connected story rather than isolated events. Brunswick Town reminds us that places accumulate history in layers, with each generation adding to the archaeological record for future visitors to discover and interpret.